Saturday, August 26, 2017

Persuasions and Adaptations

I suppose that the BBC commissioned the director Adrian Shergold and the writer Simon Burke to come up with the most recent (2007) adaptation of Jane Austen's Persuasion, but perhaps they didn't realize what a thankless task that was -- thankless, because the novel had been adapted for a 1995 movie (writer, Nick Dear and director, Roger Michell) that was in almost every way outstanding, capturing the spirit of the novel as well as a good deal of the letter. It was also unusually strongly cast from top to bottom, with Amanda Root and Ciaran Hinds (pictured above) in the leading roles, and Fiona Shaw and Simon Russell Beale in quite minor roles; it is well-paced and designed, and effectively shot. The 2007 version is a sad disappointment, though the degree to which the viewer is disappointed or satisfied will probably depend on his or her familiarity with the novel. It needs to be said right away, then, that Anne Elliott, as represented in the 2007 film bears no resemblance to the heroine of Jane Austen's novel.

This needs to be said to absolve the actress playing Anne -- Sally Hawkins -- of responsibility for the film's shortcomings. The writing and the direction in the 2007 film make Anne weepy, limp, impulsive, and undignified. In the novel, it is Anne's younger sister, Mary, to whom Austen gives these qualities. By contrast, Anne in the novel is perceptive about all around her, capable of both deep feeling and restraint, and especially aware of the degree to which her father and sisters are lacking in dignity and sense, even if her own sense of loyalty to her family and her dead mother's memory is too strong to make her openly critical of them or do anything undignified herself. All these qualities of Anne are caught by Nick Dear in his 1995 script and are beautifully realized in Amanda Root's performance as Anne -- one of the finest performances I have ever seen in a film, adaptation or not. Sally Hawkins, unfortunately, is given no chance to represent a character of such depth and interest. Readers of the novel will remember how Anne, forced by circumstance to be relatively passive in the early action of the novel, comes to learn that Captain Wentworth, whom she loved and with whom she broke an engagement seven years prior to the novel's opening, will NOT in fact marry Louisa Musgrove and is therefore "free" to form other attachments. From that point on in the novel, Anne becomes actively interested in bringing herself to Captain Wentworth's attention without coming close to "throwing herself at him," so to speak. It's a subtle move from passivity to purpose in the novel, and it is understood perfectly in the 1995 film and beautifully rendered in Amanda Root's performance. What I called "the spirit of the novel" is very much tied into Anne's character. With "her knowledge, which she often wished less, of her father's character" -- and her family's in general, it should be said -- she is the reader's surrogate in the novel, the dependable center of consciousness that keeps us interested in her fate by having us constantly endorse her judgment. All this Amanda Root obviously understands and brings to life.

The conception of Anne's character is not the 2007 film's only problem. The sequence of events at the end of the novel in which Anne and Wentworth come to an understanding that their feelings for one another have not changed is followed quite closely in the 1995 film -- it would take too long to give all the details here -- but that final action is completely changed in the 2007 version, which has Anne madly sprinting through the streets of Bath to catch Captain Wentworth, who is presented as always having just left the house to which she has run to find him. When she finally does find him, she's a sweaty and breathless mess. There is nothing -- nothing at all -- like this in the novel. Some critics of both films have complained of the public kiss that seals the lovers' reunion in both versions, and one takes the point that in Bath, c. 1814, such a public display of affection would be unlikely, but these critics' discomfort with the kiss must pale before the sight of a well-bred young woman in a long dress sprinting like a mad thing through Bath's cobbled streets in pursuit of a man. Dustin Hoffman's sprint to the church in 1967, at the end of The Graduate, is one thing. A young woman running to catch a man in 1814 is quite another.

All the other characters in the novel are more one-dimensional than Anne, but in the films, Ciaran Hinds, as Wentworth in 1995, suggests a person of substance, experience, and feeling much more effectively than Rupert Penry-Jones in 2007, who looks merely peevish for most of his film. Also in 1995, John Woodvine and Fiona Shaw (as the Crofts) and Simon Russell Beale (as Anne's brother-in-law Charles Musgrove), and Samuel West (as the younger Mr Elliott) have indelible cameos. Also, the young Musgrove sisters are more sharply distinguished in the 1995 version, and Sophie Thompson (as Anne's sister Mary) makes her character less of a caricature than is the case in 2007. The late Susan Fleetwood is a fine Lady Russell in 1995, and the excellent Alice Krige, in 2007, is just as effective.

I have some reservations about the 1995 version, especially where Anne's elder sister and her school friend Mrs Smith are concerned, but these are small matters. The 1995 film is one of the great adaptations, and (again) Amanda Root's is a performance to cherish.

Thursday, August 24, 2017

A Beethoven bargain

In the decade between, roughly, 1993 and 2003, the American pianist Stephen Kovacevich (born 1940) recorded all 32 Beethoven Piano Sonatas, and a pricey boxed set was issued shortly after the completion of the series. Now, more than a dozen years later, that set has been re-issued as a Warner Classics bargain box at an unbelievably low price, especially considering the quality of the performances. I bought some of the individual issues as they came out, and the recording quality was somewhat variable -- at times excellent, at times a bit "boomy" -- but never less than acceptable, at least to my ears. This latest re-issue does not seem to have been the result of a re-mastering, but at the price, one can hardly complain. It isn't as "bare-bones" a production as some of the recent Sony/RCA boxes, for it does contain an informational booklet and the discs are in sleeves that carry the "original cover art" (pictured above is the original cover of one of the original issues). All this is to say that, if you're into the Beethoven sonatas, you should get this. I'm not saying it's better than anything else, but it's right up there with Brendel, Arrau, Serkin,and Pollini, to name the pianists whose companies have issued recent sets, and it's in better sound than some of these. Back in the 1970's, Kovacevich recorded for Philips, and a couple or so years ago all of his Philips recordings were re-issued in a very handsome Decca box. That box includes all the concertos by Beethoven, Brahms, and Bartok, as well as some of Mozart's, and of course, there's the solo work and some chamber pieces. This box is a great bargain too, though much bigger and a bit pricier than the Warner one. Piano fans should scoop up both.

Monday, August 21, 2017

Why "All lives matter" won't do . . .

If "all lives matter," then it follows that "black lives matter," and one would expect that those who believe that all lives matter would be more than willing to join in solidarity with those who believe that black lives matter. One can imagine demonstrations and gatherings in which signs with both slogans -- "All Lives Matter" and Black Lives Matter" -- would be proudly and harmoniously displayed. This hasn't happened. Instead the slogan "All Lives Matter" has been asserted as a challenge and a reproach to the "Black Lives Matter" (BLM) movement -- almost, in fact, a kind of argument against "Black Lives Matter." So, from the "All Lives Matter" people, instead of "Black lives matter? Yes, we'll join you in solidarity!" we're getting "Black lives matter? No! All lives matter. Now, shut up!" This isn't just a bad argument -- it isn't an argument at all.

What's going on here? I would argue that it's either an evasion or (more likely) a deliberate distraction. The leap from "black lives" to "all lives" -- that is, to a higher level of generality -- is a strategy to deny the validity of BLM's response to the particular realities of a historical moment in which citizens of color believe themselves vulnerable and undervalued to an extent that citizens should never be. But there's a real dishonesty, amounting to bad faith, in this All Lives Matter strategy. The argument against "Black Lives Matter" SHOULD seek to establish that black lives are not in fact as vulnerable or undervalued as many people of color seem to think. Establishing that would involve looking at things like the murder of Trayvon Martin (and his vigilante killer's acquittal), the shootings by police of unarmed and nonthreatening African-American young men (and the acquittal of many of these shooters too), the consistent efforts over almost eight years of people like Donald Trump and Sarah Palin to cast doubt upon the legitimacy of the Obama presidency (most notoriously, the "birther" movement), and the fact that Black men are disproportionately represented in American prisons (with the associated scandals of sub-standard legal representation and overturned convictions) -- looking at all that and trying to make the case that things aren't as bad as BLM seems to think. But to respond to these circumstances only with the slogan "All Lives Matter" is morally obtuse. Imagine a German Jew in 1934, say, arranging to distribute and post in the major cities thousands of handbills reading "Jewish Lives Matter." Josef Goebbels would have been on the radio the next night saying something like "All lives matter," and telling all Germans to rest easy in their beds. And we know what would have happened after that . . .

To citizens of color, what is frightening about their position is the fact that the institutions of society that exist to protect and guarantee their security as citizens -- mainly the police and the courts -- too often seem to be complicit in injustice. There are laws on the books and adjustments to the Constitution that go back beyond the days of 1960s Civil Rights legislation to the Reconstruction years following the Civil War, and yet here we are again, at a point where a Dylan Roof can slaughter Black Americans in a Charleston church, where a politician in North Carolina can admit that voting restrictions are designed to discourage African-Americans from exercising a constitutional right, and where an American President can claim to find "good people" among neo-Nazis and white supremacists. So it's hard to deny that we still have a long way to go, that "Black Lives Matter" needs to be asserted, and that a right-wing government that panders to the even-further-right needs to be shamed into an acknowledgment of the obvious.

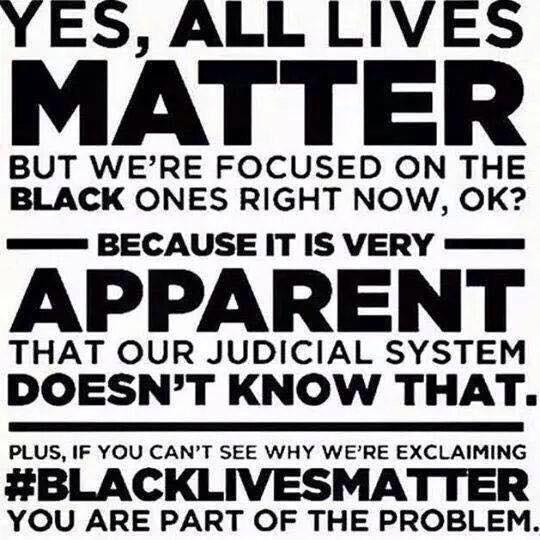

Black lives, of course, aren't the only vulnerable lives, and the BLM movement has never claimed that ONLY black lives matter. (The image above, of a BLM poster, says it all.) The mostly white Americans in Appalachia and the mid-West who have been economically dislocated by changes in the energy sector of the economy and have seen frightening rises in poverty, addiction, and homelessness demand our sympathetic attention. If they wanted to march on Washington bearing placards saying that "Appalachian Lives Matter" or "Miners Matter," who could blame them? There is a difference, though, between the source of their vulnerability and that of people of color. The main one is that there are policy solutions to the problems of economic dislocation. These solutions would not be easy -- they would require massive investments, both public and private, in education, infrastructure, health care, housing support, and new economic incentives -- investments that would require a degree of political will and moral courage that the current Republican party (and too many Democrats) seems unable to muster. The situation that "Black Lives Matter" publicizes, however, isn't amenable to a programmatic solution. It's a matter of "hearts and minds." Racism is still with us and has proved all too easy to stir up. Only when more people who call themselves conservatives can find the moral backbone to declare solidarity with vulnerable Blacks will we have taken a first step -- and only a first step -- on a better way.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)