Saturday, November 18, 2017

Goldberg v. Franken (with an update!)

Before I get to what I want to say about Michelle Goldberg's response to the Franken sexual misconduct case, I want to try to insulate myself as far as possible from the charge that as a man I have no standing to comment on or judge anything that a woman might have to say about another woman's pain when that pain results from a man's bad conduct. Michelle Goldberg is a writer with whom I find myself in agreement much more often than not, but I believe that her recent opinion piece "Franken Should Go" (New York Times, 16 November, 2017) is problematic in at least a couple of respects. I will get to these, but first, I want to say that I'm not arguing with her recommendation. I don't myself think that Mr Franken should resign from the US Senate (nor does Leeann Tweeden, the woman towards whom he behaved badly), but I can think of at least a couple of reasons why Franken might think that resignation was the best course, and I wouldn't be appalled if he did resign. Also, I'm not inclined to "blame the victim" here. Ms Tweeden was badly treated, and she says that she felt that she was at the time. I understand how, in the heightened awareness of unacceptable behavior that has followed the Cosby/Weinstein/Trump/Moore disclosures, her own experience with Mr Franken might now appear to her even more unacceptable than it was at the time, to a degree that made her want to go public with her story. I have no quarrel at all with her having done so. My quarrel -- if that's the best word -- is with Ms Goldberg in this case.

There are two points in her essay that bother me. The first, and lesser in importance, concerns her treatment of "the picture." It shows Mr Franken grinning at the camera while placing his hands on the kevlar-covered breasts of a sleeping Ms Tweeden in the course of a flight home from a USO tour of Afghanistan in 2006. Clearly, he thinks this is funny. He was at the time not a senator but a comedian, associated with Saturday Night Live. I would want to say that the picture itself really isn't the point. It gives offence only in the context of the larger narrative in which Ms Tweeden has placed it. By itself, shorn of context, it's cringe-inducing without being publicly interesting, for one can imagine circumstances in which such a picture might have seemed funny to Ms Tweeden and Mr Franken both. For example, Ms Tweeden pretending to be asleep and Mr Franken (nudge, nudge, wink, wink) pretending to "check her kevlar." Because we know that Ms Tweeden really was asleep, and that Mr Franken had already behaved inappropriately towards her, we see the picture in a very different light. I would just want to insist, though, that it's the story that counts, not the picture per se. It would seem that Mr Franken, whose behavior towards women as a Senator seems beyond reproach as far as we know, made a wrong judgment about what Ms Tweeden was willing to tolerate. It should go without saying that the same behavior towards a woman who was in a comfortable, "flirty" relationship with Mr Franken would have been a different story. It might justifiably have been a serious matter for Mrs Franken, but not for the rest of us. Some readers of this might be offended by willingness to consider other ways in which the "same" behavior (i.e. the same physical interactions) might be "read" -- but surely actions, like pictures, don't carry their meaning always on their face. Intention and context are what matters here.

My larger problem with Ms Goldberg's piece comes near the end. She writes:

"That horrifying photo of Franken will confront feminists every time they decry Trump’s boasts of grabbing women by the genitals. Democrats will have to worry about whether more damaging information will come out, and given the way scandals like this tend to unfold, it probably will. It’s not worth it. The question isn’t about what’s fair to Franken, but what’s fair to the rest of us."

The question I want to ask is, "Who are us?" Americans? women? Democrats? feminists? And the idea that "what's fair to Franken" ought to be overlooked is shocking. If Mr Franken's conduct in office has been exemplary, then fairness requires that that fact be considered in making judgments about both what he did and what he should do going forward. The political enemies of "us" (whoever "we" are) will rub our noses in that picture whether Mr Franken resigns or not. The idea that "fair[ness] to the rest of us" requires Mr Franken's resignation seems overwrought, just as Ms Goldberg's earlier plaint does: "I thought he [Franken] was one of the good guys. (I thought there were good guys.)" But we all know that there are good guys. I'm even willing to bet that Ms Goldberg knows a few.

NOTE: Some commentators have deplored Ms Tweeden's decision to "go public" on Fox News with Sean Hannity. I have no time for Hannity, but really -- if Ms Tweeden thinks that the discomfort of being "outed" on Hannity's show is what Mr Franken deserves, I'm not going to blame her.

UPDATE (11/20/17): Wouldn't you know! Two days after my having written the post above, we hear of another woman who claims to have been inappropriately touched by Mr Franken, and this time after he had taken office as Senator from Minnesota. This doesn't really change my judgment that Ms Goldberg's original article was not a well-conducted argument. I still think her handling of the photograph and her dismissal of "fairness" in Mr Franken's case undermined her argument. But it's clear too that I have to adjust my own thinking about the issue of resignation. I said above that there are arguments for Mr Franken's resignation -- arguments that he would have to consider compelling -- and, of course, these are not the same as arguments for dismissal from the Senate (which a majority of Senators would have to find compelling). I also said above that "If Mr Franken's conduct in office has been exemplary, then fairness requires that that fact be considered . . . etc. etc." In light of what we know now, we don't throw "fairness" out the window, but clearly that fairness has to be considered in relation to a different set of facts, and in light of these new facts, I am much less disposed to think that Mr Franken should continue in the Senate.

And I should credit Ms Goldberg with some prescience. She wrote that "Democrats will have to worry about whether more damaging information will come out, and given the way scandals like this tend to unfold, it probably will." At the time, I didn't know whether she was talking about Mr Franken or talking more generally. If she was thinking that a person who has behaved inappropriately toward one woman is unlikely to have so behaved towards only that single person, then this latest news seems to be evidence for that. So . . . while I still don't care for the original essay, I now say with Ms Goldberg, "Time to go, Al!" Agh!!

Thursday, November 16, 2017

Rachmaninoff seconds

Rachmaninoff's Second Piano Concerto is a gorgeous piece, less demanding of the non-expert listener than, say, the Brahms First, and posing considerable technical challenges for the pianist (though fewer, I've been led to believe, than Rachmaninoff's Third Concerto). It often seems to be a piece that young pianists at the beginnings of their careers, cut their teeth on in the recording studio. It's clearly enough of an achievement to play the thing well to get the record companies' publicity machines to crank into high gear and proclaim the arrival of the next young lion (or lioness) of the keyboard. If they can get their pianist on the cover of something like Gramophone, so much the better. In this age of being able to acquire lots of well-recorded performances of music very cheaply -- through budget reissues and purchase of used CDs -- you can buy as many Rachmaninoff Seconds as you want and not come close to bankrupting yourself. Recently, I bought three for a total of about $9.00, all in digital sound from the 1980's -- a Sony recording (originally CBS) of Cecile Licad with Abbado and the Chicago Symphony; an EMI (now Warner) of Andrei Gavrilov with Muti and the Philadelphia Orchestra; and a Decca recording by Christina Ortiz, with Moshe Atzmon and the Royal Philharmonic. All are studio recordings, and I checked them in my listening against Stephen Hough's more recent live recording with Andrew Litton and the Dallas Symphony, on Hyperion. I really like Hough's account -- it is excitingly paced without ever seeming rushed, and the recording captures amazingly well the varied colors of Hough's playing. It's not just a wash of gorgeous sound; it's alive minute by minute, and very fresh. When Hough recorded it in 2004 he was already a well-known "star" pianist. Of the pianists in the recordings mentioned above, two were just setting out -- Ortiz (from Brazil) and Licad (from the Philippines) -- while Gavrilov had about a decade of recording under his belt. All three had won prestigious competitions.

I had two surprises in listening to this trio of recordings. First, I was disappointed in the Licad/Abbado recording, and that was a surprise because I very much like a Saint-Saens Second that Licad made with Previn around the same time. My disappointment was with the sound first and foremost: the orchestral sound was thick and its relation to the piano was murky. With the piano itself, the sound seemed bass-heavy. The overall effect was leaden -- not what one usually gets with Abbado. I was reminded that I didn't like the sound of his Sony Tchaikovsky recordings from Chicago (although Deutsche Grammophon got good results with him there, especially in Mahler). The Gavrilov/Muti recording was a pleasure -- nothing fancy, just nice sound and good balance, reminding me other recordings I had enjoyed, like Vasary's and Guttierez's (on DG and Telarc respectively). The pleasant surprise, though, was the Ortiz/Atzmon recording, with a lot of air round the sound and an almost chamber-music-like intimacy between orchestra and soloist. It's a very lyrical recording, with no highlighting of the virtuosity and paced more relaxedly than Hough's. It's not slack, though, and the sound is very inviting. Adding to its charms are the unusual pairings. Gavrilov and Licad feature the Rhapsody on a Theme by Paganini -- almost a default pairing for this concerto, and, of course, it's a lovely piece. Still, it was nice to hear Ortiz work through Addinsell's so-called "Warsaw" concerto (film-music very much in the Rachmaninoff vein) and Litolff's Scherzo. The most unusual feature was her rendering of an arrangement of Gottschalk's variations on the Brazilian national anthem, obviously an oblique tribute to Ortiz's own heritage. The pairings are pretty lightweight, but no less charming for all that.

Saturday, November 11, 2017

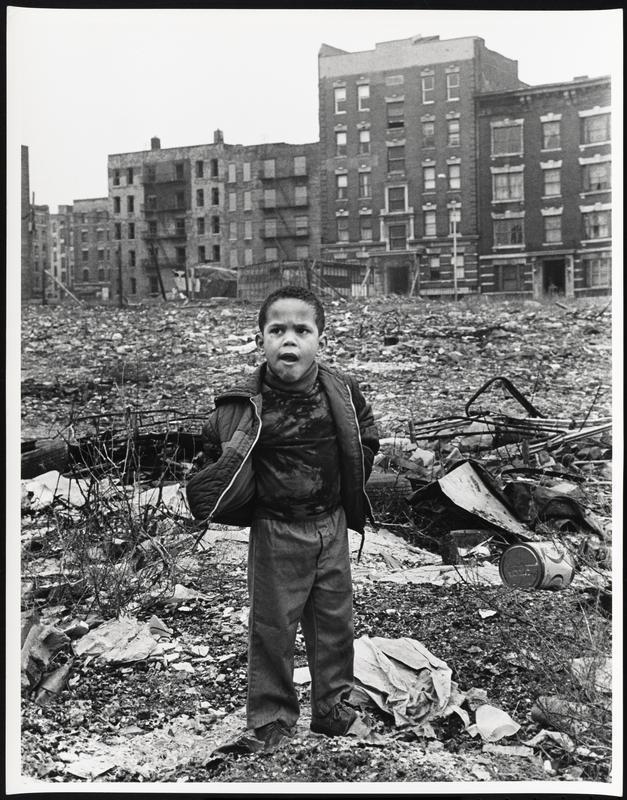

a memory of mel rosenthal

A couple of days ago, I was taken aback when I saw the substantial obituary for the photographer Mel Rosenthal in the New York Times. Our paths had crossed briefly about 45 years ago, and I had thought about him occasionally since, but I hadn't known of his success and reputation as a photographer in New York. It was heartening to hear of it, even though it was sad to hear of his death. [That's one of his South Bronx images, above.] I was teaching English at Vassar in the early 1970s and trying to write my doctoral dissertation. Mel had been in the department a few years -- he was four years older than I -- and he wasn't long for that world. Vassar had begun to admit men in 1969, the year before I started there, and the powers-that-were in the English Department at that time were largely older single women, not far from retirement, with a couple of middle-aged men just below them in length of service. The college was changing, the country was in the throes of anti-war and civil rights disturbances, the academic job market was beginning to tighten, and the atmosphere was tense. There were some very smart younger people on tenure-track, and there were others like me who were on a three-year contract with prospects of a second, and mostly my memory is of the younger generation keeping their heads down, being appropriately deferential, and beavering away to establish themselves in the profession. Only two people in any way ruffled the surface: Harriett Hawkins, sharp as a knife and flamboyant as hibiscus, had a book out from Oxford University Press and was untouchable; Mel Rosenthal, direct, outspoken, aware of a larger world outside the college, was more like an irritant. In department meetings, he spoke out in the sterile arguments about things like "the integrity of the two-semester course," and spoke with the confidence of himself as the intellectual equal of anybody in the room. I wouldn't say he was rude, but he didn't do deference. He had a sense that the department could be doing some more interesting things in addition to the then-standard canonical stuff that comprised the bulk of the curriculum and he wasn't afraid to say so. I have to say that I know nothing about his effectiveness as a teacher or whether or not he had potential as a literary scholar. I had been at Vassar a year or two when he was fired. In a famous scene, he stormed out of the (male) Chair's office after having been "let go," and, to the horror of the genteel department secretary, flung back over his shoulder a couple of obscenities and the word "pipsqueak."

At the end of my first year at Vassar, the English Department hired a young black man (I'll call him Fred) whose field was 18th Century literature. He arrived in the summer before he was due to start teaching -- I think the summer of 1971, but maybe 1972 -- and almost immediately suffered some kind of psychological or emotional collapse. I never did hear the official diagnosis. At that time, my wife, Janis, and I were living in college housing at the back of the campus near the golf course in a building called Palmer House that comprised five or six apartments, and Fred was to live in one of them, next door to us on the second floor. At first, he seemed friendly and a bit reserved, but it wasn't long before we found him one day cowering in a corner of a room in his yet hardly-furnished apartment, apparently terrified of something. Shortly thereafter, he was picked up one night by the college police, out of doors near our building and shouting into the darkness. Some nearby neighbors had heard him (we hadn't) and called the police about the disturbance. When we next saw Fred, he was in some kind of facility, in downtown Poughkeepsie, I think, and undergoing treatment.

Janis and I went down to see him with a friend, Tom Duddy, who was also a friend of Mel's, and when we got to the hospital, Mel was already there. I have a memory of a large room with green vinyl-topped tables and cream walls. The tables were bolted to the floor, and so were the chairs, so that when one sat down, it was impossible to pull up the chair or pull the table closer. Fred sat in a chair, subdued and, I assume, medicated. He seemed embarrassed, maybe ashamed, and had little to say. It was uncomfortable. Janis and I had certainly never seen anyone in such a condition or in such a place, and it was hard to find words. I have no idea what we said. I do remember that, of the four visitors, Mel was the one who found the most to say, and I was struck by his directness and gentleness. For all I knew, he was as uneasy as the rest of us, but he found a way of trying to engage Fred constructively. He had no illusions, though -- as became clear as we were leaving -- about the likelihood of Fred's taking his position at Vassar. The blend of gentleness and clear-sightedness was what I've remembered on the occasions over the last four decades whenever I was reminded of Mel, which wasn't all that often because I hadn't been close to him.

I don't know what happened to Fred -- a severance with Vassar was arranged -- and I didn't know, until I read his obituary, what had happened to Mel. I'm pleased, though, that he was successful and respected. He was a good man, and I like to think that his work is in some way consistent with the behavior he exhibited that day in that miserable green-and-cream room.

Wednesday, November 8, 2017

Well, at least it wasn't "Ishtar" . . .

In the annals of movie failures, Elaine May's Ishtar (1987) holds an honored place: it took in at the US box office around $35 million dollars less than it cost to make. That doesn't mean that it was a bad film, and since I haven't seen it, I offer no opinion on that. But David Lynch's Dune (1984), which lost a mere $10 million by comparison, certainly is a bad movie, and it seems remarkable to me that seven years after the kinetic and charming original Star Wars anyone could have thought that this exercise in static grandiosity would enchant anyone. In 1980, Dino De Laurentiis had produced Flash Gordon, another kinetic and charming movie, sillier and sexier than Star Wars, and making no pretensions to seriousness. That movie made great use of Max von Sydow, who had a high old time as Ming the Merciless. Four years later, Rafaella De Laurentiis, Dino's daughter, produced Dune, in which von Sydow, in a very minor role, has maybe about ten minutes onscreen . . . Dino himself (who died in 2010 at 91) had originally acquired the rights to Frank Herbert's novel and had tried to interest Ridley Scott in the project. Scott worked on a script, but eventually gave it up to make Blade Runner (1982), a genuinely great and moving sci-fi movie.. The eventual director, David Lynch (who went on to his own distinctive successes) has more or less disowned the movie, admitting that he should never have accepted the project from the start because he knew that he wouldn't have control over the final cut.

So what's wrong with it? That's not too difficult to say. It's bad in the way that Zeffirelli productions can sometimes be bad -- lots of money spent on elaborate sets and not nearly enough happening in front of these sets. The sets are indeed impressive; from the palatial interiors to the desert landscapes, they look good, and the costuming budget must have been considerable. The costumes blend pseudo-medieval ornateness with a sci-fi leather look as needed, and then there are the Bene Gesserit witches, who look like punked-up nuns and who seem to have the power (whether before or after conception I don't know) to determine the sex of their children. But a movie has to do more than appeal to the eye. The plot counts for something, and this one is unnecessarily complicated, requiring an intermittent voice-over narration, by a character who seems to have no part in the plot, to keep us straight. The dialogue is stiffly oracular -- no one speaks like a real person, and it's no defense of this to say that they are not real persons. As for characterization . . . forget it. One remembers that the first Star Trek movie (1979) suffered from the combination of impressive sets and leaden pacing, but at least there the dialogue was plausible. James Kirk talked like the Kirk we knew and loved, and, bad though the movie was, it netted over $90 million at the box office in the US. 1982's Star Trek: The Wrath of Khan was much more fun, though it netted a mere $86 million. It still puzzles me how, in the context of all these other films mentioned above, someone didn't point out that some plausible dialogue and peppier action were needed. Only the evil and over-the-top Baron Harkonnen (Kenneth McMillan) seems to be having any fun.

The cast can't be faulted. Kyle MacLachlan, Patrick Stewart, Jurgen Prochnow, Francesca Annis, Sting, von Sydow, Silvana Mangano, Sean Young, Dean Stockwell, and others are all solid professionals, and one can only hope that they weren't counting on a percentage of the profits for their remuneration. The plot is dressed-up standard bad-people-want-to-take-control-of-the-universe stuff, framed as a dynastic struggle, and what has to be done to take control -- which involves getting ones hands on the spice-mining operation on the desert planet Dune -- requires a lot of exposition that really clogs the pacing. The threats to spice-mining are the sand-worms of Dune, which respond to rhythmic stimuli by attacking and which have to be distracted by "thumpers." However, it turns out that drinking the water of life (sorry: "Water of Life") gives one control over the sandworms, and the climactic battle has the good guys (MacLachlan and his troops) riding the sandworms against the enemy. The trouble is that sandworms don't move fast -- they're huge things, each of which can carry a small regiment on its back -- so the whole effect of the climax is like slow-motion water ballet. I have to say that I kind of liked the sandworms . . .

One other aspect of the movie bothered me. There's a kind of pseudo-religious undercurrent to it all that doesn't really make any sense. There seems to be something of a prophecy that a Special One will come -- or maybe has already come, and maybe it's Paul Atreides (Kyle MacLachlan), who seems to seal the deal by drinking the Water of Life without dying as a result. But then, all that happens is that he can control the sandworms. He already has an army -- the enslaved Fremens, the denizens of Dune, who had been forced to work in the spice mines until Paul came along -- and a creepy little sister who, with Gesserit powers even at an early age, does things that suggest she could take care of the whole business without Paul having to lift a finger. Paul, at the end, kills the evil enforcer Feyd-Rautha (Sting, no less! see image above) in single combat, and we're to understand that the long arc of the moral universe has completed its circle. The religious undertones to this are very different from those at the end of Star Trek: The Motion Picture, but in neither case do they redeem a pretty lifeless movie

Some readers of this might think that this movie must be so bad that it's good, or that it is a deliberate sending-up of the sci-fi genre. I've actually entertained this idea, but surely a send-up just has to be livelier (and shorter)? Be all that as it may, you can now pick it up pretty cheaply on DVD, so give it a try. But try to see first every other movie (except Ishtar, maybe) mentioned above, and then tell me that I don't have a point. Why couldn't the De Laurentiises just have packed it in after 2001, Star Wars, and Blade Runner showed what could be done with the genre?

Sunday, November 5, 2017

The wisdom of age?

The other day, I read a very complimentary review of a Beethoven concert conducted by Herbert Blomstedt (b.1927), a Swedish-born conductor best known in the United States for his recordings with the San Francisco Symphony in the late 1980s and early 1990s. He was already in his sixties when, it seems, he was "discovered," and, although he is hardly a household name even today, his recordings of the six Nielsen symphonies with the SFO are probably as good as any in the catalogue. Blomstedt is now 90, and, to judge by the review I read, still at the top of his game. I own his recordings of the Nielsen symphonies (on two "Decca Double" issues), and they sound wonderful. They are the only Blomstedt recordings I own. Another conductor who was a "late bloomer" in the publicity stakes was Gunter Wand (1912-2002). His digital recordings of the Bruckner symphonies, started when he was around 70, received wide praise, and he was touted as the premier Brucknerian of his time. I don't know whether he is or not, but I felt guilty about not owning any of his recordings, so I picked up a used copy of a live concert comprising the Beethoven Fourth Symphony and the Mozart "Posthorn" Serenade, conducted by Wand when he was 89 [see image above]. I'm happy to have it. The performances are propulsive, and my only reservation is that the orchestral sound isn't as "warm" as some other recordings I have -- recordings almost all made under studio conditions. His orchestra on that recording, the Hamburg-based NDR Symphony, might be not quite as polished as, say, the Berlin Philharmonic, but there's nothing sloppy or compromised about their playing. Their Beethoven Fourth is as engaging and energetic as any I've heard, and my only reservation about the "Posthorn" is that I wished the posthorn itself could be a little bit more prominent in the aural mix. I've always liked George Szell's Cleveland recording of that serenade, and there the posthorn has its say, so to speak, but on the whole, the present digital sound of Wand's recording is something I wouldn't want to be without. Likewise, much as I enjoy Eugen Jochum's Concertgebouw recording of the Beethoven Fourth (from the 1960s), Wand's more present and open sound, live recording conditions notwithstanding, is very attractive. Wand's Bruckner recordings from Cologne are now re-issued in a Sony budget box, for $22.00 for nine discs! I'm tempted -- but with complete sets from Jochum (EMI), Karajan, and Haitink, do I, at age 73 myself, really need them?

Neither Wand nor Blomstedt, of course, were really "late bloomers," They were very fine conductors for a long time who just didn't have the good luck to be picked up and publicized by major labels when they were in their thirties or earlier, as Simon Rattle, Gustavo Dudamel, Bernard Haitink, and Lorin Maazel were. Haitink is now pushing 90 himself, but he he has been in the public eye, and deservedly so, since 1960 or so. Still, it would be hard to make the case that he is objectively a "better" conductor than Wand or Blomstedt. The same holds for Christoph von Dohnanyi, born, like Haitink, in 1929, who was better-known earlier than Wand or Blomstedt, and whose Beethoven recordings are preferable, to my ears, than Haitink's -- maybe for reasons having more to do with Telarc 1980s sound than anything else. Record magazines love to "rank" things -- conductors, recordings, equipment. You've seen their top-ten and top-fifty lists. I say, ignore them. In this age of cheap used CDs with excellent sound, buy promiscuously and listen for yourself, and trust your ears There's more good stuff out there than you know.

Saturday, November 4, 2017

Mike Leigh's view of life on the dole

Mike Leigh made Meantime for BBC's then-new Channel 4 in 1983, and the story goes that it would have vanished without trace had it not been for a few viewers who were impressed enough to tape it from the broadcast and bootleg it among their friends, Now it has found its way to the Criterion Collection, in a print that still suffers a bit from its original 16-millimeter format -- i. e. the picture is a bit less sharp than we've come to expect from movies today -- but if that doesn't worry you, and if you like Mike Leigh's work, then this is well worth a look. Set in the East End of London during the Thatcher years, it offers a painful look at life on the dole. The cast is remarkably strong -- Tim Roth, Gary Oldman, Alfred Molina, Marion Bailey, Phil Daniels, and Pam Ferris all do memorable work -- and the cinematography captures the interiors and exteriors of depressed East London in a way that complements perfectly the states of mind of its denizens.

There is no real back story. We're just faced with the immediate circumstances of the Pollocks -- Mavis and Frank, and their teenage sons Mark (Phil Daniels) and Colin (Tim Roth) -- in their poky flat, with its dodgy windows and sub-standard washing machine. No one in the family works -- the men live on government handouts, even though it soon becomes clear that Mark, at least, is sharp and capable. The parents are feckless, beaten down, and Colin is "slow," in vivid contrast to his brother. Tim Roth's unshowy representation of Colin is painful and gripping. A late scene in which Mavis (Pam Ferris) berates Colin for failing to take up an offer of work that her suburban sister Barbara (Marion Bailey) has made is as painful and true as anything I've seen in movies -- if one were to walk in on a situation like that in "real life" (and it's a very plausible scenario), one would be embarrassed and pained. And yet, that scene and its aftermath help us understand something about Mark that we hadn't been sure about up to that point -- and maybe Mark hadn't been sure about either -- and something about the monosyllabic Colin too, at the very end. For all that, these are characters literally with nowhere to go. Mark talks of "getting away," but there's clearly no away to get to.

It seems that Mavis's sister Barbara has made an escape -- she took a secretarial course in a local college, got a job in a bank, and married "up" -- or at least "up" a bit. Her husband John (Alfred Molina) works in a bank branch too, and they live twelve miles out in the suburbs in a more spacious but far from luxurious house. Their marriage is childless, and there seems to be no deep affection between them. Barbara's offer of a job to Colin -- some interior painting at her house -- could be exploitation (the wages are small) or an act of kindness. Does she know herself? In the middle of the movie, she seems positive, energetic, articulate, and attractive in the scene at Mavis's flat when she makes the job offer. By the end of the movie, she has collapsed in a drunken slump by the time John comes home from work. John seems neither unkind nor abusive, and one wonders if what we see in Barbara is a consequence of her having married to "get away," without particularly thinking of her compatibility or otherwise with the man she has married. Mavis and Frank are trapped, but Barbara, in the suburbs, clearly feels herself in a bind too.

Hovering on the edges of the family story are two East End characters who extend the sense of entrapment beyond what the Pollock family drama shows. These are the skinhead Coxy (Gary Oldman), whom Colin finds impressive, and Hayley (Tilly Vosburgh), a neighborhood girl that Colin fancies and who clearly feels sorry for him without being really interested in him. These two roles are little more than cameos, but the actors make them vivid. Coxy is a mass of anger and a physical impulsiveness that looks like attention-deficit disorder, curiously threatening and yet helpless. Hayley, like the other women in the movie, is depressed, and the camera catches her in scenes in which she seems tightly confined. In the only slightly hokey moment in the film, we see an image of Coxy playing inside an empty oil barrel [see the image above], for all the world looking like a laboratory rat in a wheel in a cage. It's plausible, given what we've seen of Coxy's edgy physicality, but it maybe too obviously points up the central conceit of the movie.

By the end, nothing is solved, but these characters and their circumstances have been made known to us, to the extent that they can be. One might be tempted to complain, as some early viewers apparently were, by the lack of a more explicit political "message" -- Mrs Thatcher is never mentioned, though we do see a view of Whitehall from Trafalgar Square -- but that would add nothing to our engagement with and understanding of the Pollocks and their problems. The film works just fine as it is.

Tuesday, October 31, 2017

Versions of Emma . . .

For me, Emma is the novel in which Jane Austen comes closest to George Eliot. Like Middlemarch, Emma has an impercipient heroine who wishes to do good and who, in the effort do good, makes mistakes that force her to re-evaluate her sense of what the good entails. Emma is much less given to introspection than Eliot's Dorothea Brooke, and the lessons that experience teaches her are therefore perhaps less painful and certainly less likely, given Emma's wealth and status, to affect her place in the social world, but they are serious nonetheless. She is the only Austen heroine that one can accuse of cruelty herself and of being blind to the cruelty of another. Blinded to some extent by rank and wealth, she is also perhaps the only Austen heroine to be blinded too by a jealousy that she is incapable of articulating or acknowledging. So Emma is a sobering novel, and all the more sobering because the protagonist is active and intelligent, and not at all like the more passively suffering, morally sensitive Fanny Price of Mansfield Park. We certainly sense that harm might be done to Fanny -- but with Emma, there's the active doing of harm that's all the more dangerous because it goes unrecognized for so long. The harm she does isn't just a matter of trying to make inappropriate matches for her protege Harriet Smith, the young woman whom she encourages to think it likely that men of a very different class might marry her -- although trying to run people's lives is bad enough. Worse, though, is her abetting of Frank Churchill's disparagement of Jane Fairfax, a young woman of no family (as Emma might say) but one who is clearly Emma's equal in beauty and her superior in musical talent.

The situation. readers will remember, is as follows: Frank Churchill is engaged to Jane but cannot make the engagement public for fear that his aunt, who brought him up and whose name he took, might disinherit him for a connection with a woman she believes to be beneath him. Jane is an orphan whose only relations are the poor Bateses. In Highbury, the village where the novel is set, Emma, her father, and their neighbor at Donwell Abbey, Mr Knightley, are very much at the top of the social tree. They are not "titled" aristocracy, but in their small world they are the de facto aristocrats, the setters of the standards of taste and manners, who expect, and receive, the respect of the neighborhood. When Jane Fairfax and Frank Churchill are in Highbury at the same time, Frank's strategy for concealing their engagement is to pay a lot of attention to Emma and, in doing so, to constantly disparage Jane, usually by making or implying comparisons with Emma, tacitly inviting her to believe herself superior to Jane in the ways that matter to Frank. His attention to Emma is public; his disparagement of Jane occurs in private conversation with Emma, who does not seriously try to reprove Frank for it. Indeed, she's flattered by it, and all the more so since Jane's relative, Miss Bates, has constantly irritated Emma by talking about Jane's beauty and accomplishments. So there's a worm of jealousy that Frank's flattery of Emma and disparagement of Jane feeds, and I think we have to understand the climactic scene of the narrative -- where Emma publicly insults Miss Bates by making a joke about her being boring and dull -- as connected both to her irritation with Miss Bates's focus on Jane's qualities and to her sense, that Frank has encouraged, that Jane isn't really all that special. Mr Knightley is present at the scene of insult, and he tries to mute the pain of it for Miss Bates, but later, in private conversation, he reproaches Emma severely for her behavior. He doesn't know, of course, the full extent of Emma's abetting of Frank's disparagement of Jane. If he did, he would, we can imagine, be even more blunt in his condemnation of Emma's behavior. He sees Frank only as a lightweight who doesn't know his duties to his father -- but Emma has experience of his conduct that extends beyond that and in which she is complicit -- something that she at no point admits to Knightley, even after her own conduct improves. In Middlemarch, Dorothea's moral growth comes with self-analysis and self-reproach. Emma, less introspective, requires some help from the outside, so to speak, and that's what Knightley provides. He has long loved Emma, but he doesn't declare that love until Emma has shown due awareness of the harm she has done and is sorry for it.

Any filmed version of Emma should try to do justice to its core of moral seriousness. I haven't (yet!) seen every filmed version, but I've seen the most recent three. Two are "stand-alone" movies from 1996, with Gwyneth Paltrow and Kate Beckinsale respectively in the title role. The most recent is a 2009 BBC series, with Romola Garai as Emma. All will give pleasure, but I don't think that all work equally well. The two movies time out at 107 minutes (Beckinsale) and 120 minutes(Paltrow), while the series, originally in four episodes, comes in at just under four hours -- in effect, twice as long as the others. From my point of view, as someone looking for a version that does justice to the novel, the series has a considerable advantage -- the details of the plot are clearer, relationships are well-established, and we live with the characters long enough to more fully understand them and the changes they undergo. A viewer who has not read the novel might well not be bothered by what sometimes seems to me a hasty treatment of some of the developments, and that's fine. And in this case, there is much that I do like about the series -- but its effectiveness for me is compromised by the director Jim O'Hanlon's conception of Emma herself. I don't think it's the fault of Romola Garai [pictured below, as Emma], who did excellent work in the BBC serialization of Daniel Deronda (she was Gwendolyn Harleth) and in the newsroom thriller series The Hour. In what follows, I'll discuss what struck me as the strengths and weaknesses of each of the three versions.

1. BBC series (2009).

There are two great strengths to this version. One is the scene-stealing performance by Michael Gambon as Mr Woodhouse, Emma's widowed, valetudinarian father, who is almost paralyzed by his fears for his own health and those of people he cares about (so he's not totally self-centered). It's a one-dimensional role, but Gambon is so alive and droll and charming that it doesn't pall. (I once saw Gambon on stage as Eddie Carbone in Miller's A View from the Bridge, very credible and scary, despite some slippage of the Brooklyn accent, and as far as could be from Mr Woodhouse.) Of the three Mr Woodhouses I'm considering here, he's the one for whom Emma's love and concern are most credible, and that's thanks to Gambon. More important, though, is the other strength -- the length of the series enables us to more fully appreciate the insensitivity that approaches cruelty in Frank Churchill's treatment of Jane Fairfax. In having to disguise his engagement to Jane, Frank's strategy, as I explained above, is to treat her disparagingly while showing a decided and quite public interest in Emma herself. Emma, to her discredit, goes along with this disparagement and seems even to enjoy it, though it's obvious that Jane is at least her equal in beauty and her superior in musical talent, even if she is a penniless orphan. Already resentful of Miss Bates's attention to Jane, Emma is completely snowed by Frank's deceit, and for a long time she even fancies herself in love with him. The two actors playing Jane and Frank, Laura Pyper and Rupert Evans -- names unknown to me until now -- are very effective, and Pyper especially makes Jane's suffering convincing. I think it's critical to our estimation of Emma and to our understanding of the moral force of the narrative to see as much as we do of the Frank-Jane relationship and its complications. What's galling about Frank, though Emma never seems to notice the impropriety of it, is Frank's obvious enjoyment of this game of disparagement. That's because Frank is witty and charming and draws Emma into enjoying it too.

My reservations about the conception of Emma herself in this version might be put this way: Emma is too like Harriett Smith, the protege whose romantic life Emma undertakes to manage. Harriet (Louise Dylan) is a pretty, good-hearted, not-very-bright girl, and her limitations are indicated by the readiness with which she accedes to Emma's ideas about her marital prospects. But Emma herself should not appear to be so silly -- she should (and in the novel does) understand that she is seeking to move Harriet into a higher social class and that doing so might prove painful to Harriet. But in this version Emma comes across as a rather empty-headed giggly "fixer" whose main difference from Harriet is the fact that she, Emma, has rank and money and the power that goes with them. In the novel, Mr Knightley's attraction to Emma derives in part from his perception of her her intelligence, a quality she undervalues or fails to acknowledge in herself, and it's important that in a filmed version this intelligence be somehow made manifest. In this version, however, Emma's matchmaking comes across not as a misuse of intellect but as mere meddling. Consequently, the scenes of Emma's dawning moral awareness lack the force that they could have.

One curious feature of this version is the opening, with its "backstories" that explain how Frank Churchill and Jane Fairfax came to be isolated from their respective families as children. I'm not sure how this is supposed to work, unless to suggest that Frank's bad behavior later is to be explained as a response to the childhood trauma, for Frank has always known the identity of his father. That father is Mr Weston, a neighbor of Emma and her father, who in the opening of the novel (and the other filmed versions) marries Anne Taylor, Emma's governess-companion. When a young widower and in difficult financial straits, he had given Frank up to be cared for by his sister-in-law, who insisted on the change of name to Churchill and who brought Frank up in very comfortable circumstances. Are we meant to see Frank's bad behavior as somehow intended to punish, by embarrassing, his father for "abandoning" him?

The rest of the cast is just fine, although there are more vivid performances of some of the supporting characters in the other versions. Mr Knightley is played by Jonny Lee Miller, very much against his Trainspotting type. He's effective enough, though perhaps not credibly sixteen years older than Emma -- Miller is in fact nine years older than Garai, who was in her mid-twenties when this Emma was filmed. Jodhi May, as Miss Taylor, is arguably too young for the role. In Daniel Deronda, where she appears again with Romola Garai, she is Garai's romantic rival. I think that she should be at least as old as Mr Knightley -- 38 in the novel -- but still younger than Mr Weston, whose wife she becomes. Of the others, Tamsin Grieg is a very effective Miss Bates, and Christina Cole a Mrs Elton that you love to despise -- even as perhaps you uncomfortably realize that she is, in many ways, a lot like Emma in her belief in her organizational powers.

Gwyneth Paltrow as Emma (1996)

The conception of Emma in this film version is much closer to that of the novel and, to that extent, preferable to that of the BBC serial discussed above. There is no doubt, either, that Emma is NOT just a giggly girl like her protege Harriet. The Harriet here is Toni Collette, a very fine actress [pictured above, with Paltrow], and the contrast between the sharp Emma and the dim but good-natured Harriet is perfectly clear. On the whole, Gwyneth Paltrow is a credible Emma -- she is not the most expressive of performers, a bit bland even, but then Emma is a character who sails through much of her young life untroubled by doubts about her motives or her machinations, and Paltrow's untroubled demeanor seems apt for much of the film. The big scene where she doesn't quite rise to the occasion is that of Knightley's declaration of love, where Jeremy Northam's rendering of Knightley's confusion and affection is credibly animated, while Paltrow doesn't seem able to find a matching animation in her own features. Three other women in the cast give more vivid performances -- Toni Collette, already mentioned, as Harriett, Sophie Thomson as a painfully vulnerable Miss Bates, and the great Juliet Stevenson as a surprisingly knowing, witty, and even likable Mrs Elton. There's also the accomplished Greta Scacchi as Mrs Weston, though her part, as written, doesn't give her enough to do.

As the list above suggests, there's an "all-star-cast" quality to this production, and it extends even to the score, by Rachel Portman. That's not to say that all roles are equally convincingly taken. The young Alan Cumming is too devoid of unctuous nastiness for Mr Elton, though he's always fun to see, and Ewan McGregor seems a bit uneasy as Frank Churchill. As I've already suggested, though, the Frank-Jane part of the story, with its important moral relationship to Emma herself, is diminished in this and the other film version, presumably in order to keep the film at a length deemed appropriate for showing in cinemas. Jeremy Northam is an effective, polished Knightley. Denys Hawthorne is an effective Mr Woodhouse, though less vivid than Michael Gambon in the role, and Polly Walker is fine as Jane Fairfax, even as one wishes that the full extent of her humiliation by Frank, and Emma's complicity in it, could have been developed more fully. The Frank-Jane story is much more than a sub-plot in the novel, for without a full treatment of it, we can't appreciate Emma's capacity for doing harm. That whole dimension is underplayed in this film, and together with Gwyneth Paltrow's blandness at crucial moments, it leads this version to be less morally engaging and affecting than it could have been.

Kate Beckinsale as Emma (1996)

As with the Paltrow version, this almost contemporaneous film also fails to give full weight to the Frank Churchill-Jane Fairfax story, the importance of which is to show us Emma's complicity in Frank's cruelty. In compensation, though, it does give us the most engaging accounts of Emma and of Mr Knightley, both given performances of great effectiveness. Kate Beckinsale's face, in repose, has a severity that suggests a person not altogether at ease with herself. She plays Emma as a character who could know that she is capable of using her intelligence and ingenuity to better effect than arranging the romantic lives of third parties in a small village. She comes across as not totally happy with herself even before the moral problems attendant on her meddling begin to be clear. It's fitting, then, that the Mr Knightley in this version, played by Mark Strong [pictured above with Beckinsale], is the severest and angriest Knightley of the three I'm considering, and to my mind the most effective. His Knightley is a blunter, less suave, more intense character than Jeremy Northam's, and his critical interventions with Emma -- with respect to both her meddling with Harriet's life and her climactic public insulting of Miss Bates -- have great dramatic force, and their impact on Beckinsale's Emma is palpably conveyed.

The rest of the cast is solid or better. Samantha Morton is as effective a Harriet as Toni Collette, and Prunella Scales -- yes, Sybil Fawlty from Fawlty Towers -- is a fine Miss Bates, older than the character in the other two versions and the more seemingly vulnerable for it. Scales was in her mid-sixties when she played Miss Bates, thirty years older than Sophie Thomson and Tamsin Grieg in their respective versions. Raymond Coulthard is a confidently assured young prig as Frank Churchill -- more at ease in the role than Ewan McGregor -- and Olivia Williams suggests a Jane Fairfax of considerable strength and dignity.

Some reviewers of this version saw it as an unusually "dark" film for an Austen adaptation. One can see their point, but that should not be seen as a criticism: rather it should be seen as a tribute to the film-maker's perception of the novel's moral seriousness. Austen is by no means always as "light and bright and sparkling" as she feared she was in Pride and Prejudice, and even in that novel, it's a mistake to see it as merely a frothy entertainment. If you want darkness in Austen adaptations, there's also the splendid and disturbing 2007 film of Mansfield Park, very strongly cast and directed by Patricia Rozema.

Epilogue: "But what about Clueless . . . .?

"Light and bright and sparkling" would do very well to describe Amy Heckerling's 1995 film, Clueless, but it shouldn't be taken as a version of Emma. The moral seriousness at the core of Austen's novel -- it's concern with impercipience that enables cruelty -- is totally excised. Plot elements are certainly borrowed from Emma, but the setting is moved to a California high school in an upscale neighborhood, and the Emma-like character, called Cher in the movie, is 16, where Emma is 21 or 22. Certain stereotypes of American teenagers are added to the mix, and it's all played for laughs. One of the big jokes on Cher is that her privileged self-confidence that derives from wealth blinds her to the fact that a boy she fancies, Christian (a parallel to Frank Churchill), is gay -- something that everyone else at her school seems to know. Still, the writing, also by Heckerling, is excellent, a mix of literary and pop-cultural allusion, high-school slang, and verbal invention ("As if . . .!") that the cast carries off just perfectly. Alicia Silverstone is the valley-girl incarnate, and if it's froth, the movie knows exactly what it's doing. Stacey Dash and Brittany Murphy as Cher's sidekicks [above , with Silverstone] -- with Murphy in the Harriet role -- are perfect partners. On it's own terms, the film works perfectly.

The situation. readers will remember, is as follows: Frank Churchill is engaged to Jane but cannot make the engagement public for fear that his aunt, who brought him up and whose name he took, might disinherit him for a connection with a woman she believes to be beneath him. Jane is an orphan whose only relations are the poor Bateses. In Highbury, the village where the novel is set, Emma, her father, and their neighbor at Donwell Abbey, Mr Knightley, are very much at the top of the social tree. They are not "titled" aristocracy, but in their small world they are the de facto aristocrats, the setters of the standards of taste and manners, who expect, and receive, the respect of the neighborhood. When Jane Fairfax and Frank Churchill are in Highbury at the same time, Frank's strategy for concealing their engagement is to pay a lot of attention to Emma and, in doing so, to constantly disparage Jane, usually by making or implying comparisons with Emma, tacitly inviting her to believe herself superior to Jane in the ways that matter to Frank. His attention to Emma is public; his disparagement of Jane occurs in private conversation with Emma, who does not seriously try to reprove Frank for it. Indeed, she's flattered by it, and all the more so since Jane's relative, Miss Bates, has constantly irritated Emma by talking about Jane's beauty and accomplishments. So there's a worm of jealousy that Frank's flattery of Emma and disparagement of Jane feeds, and I think we have to understand the climactic scene of the narrative -- where Emma publicly insults Miss Bates by making a joke about her being boring and dull -- as connected both to her irritation with Miss Bates's focus on Jane's qualities and to her sense, that Frank has encouraged, that Jane isn't really all that special. Mr Knightley is present at the scene of insult, and he tries to mute the pain of it for Miss Bates, but later, in private conversation, he reproaches Emma severely for her behavior. He doesn't know, of course, the full extent of Emma's abetting of Frank's disparagement of Jane. If he did, he would, we can imagine, be even more blunt in his condemnation of Emma's behavior. He sees Frank only as a lightweight who doesn't know his duties to his father -- but Emma has experience of his conduct that extends beyond that and in which she is complicit -- something that she at no point admits to Knightley, even after her own conduct improves. In Middlemarch, Dorothea's moral growth comes with self-analysis and self-reproach. Emma, less introspective, requires some help from the outside, so to speak, and that's what Knightley provides. He has long loved Emma, but he doesn't declare that love until Emma has shown due awareness of the harm she has done and is sorry for it.

Any filmed version of Emma should try to do justice to its core of moral seriousness. I haven't (yet!) seen every filmed version, but I've seen the most recent three. Two are "stand-alone" movies from 1996, with Gwyneth Paltrow and Kate Beckinsale respectively in the title role. The most recent is a 2009 BBC series, with Romola Garai as Emma. All will give pleasure, but I don't think that all work equally well. The two movies time out at 107 minutes (Beckinsale) and 120 minutes(Paltrow), while the series, originally in four episodes, comes in at just under four hours -- in effect, twice as long as the others. From my point of view, as someone looking for a version that does justice to the novel, the series has a considerable advantage -- the details of the plot are clearer, relationships are well-established, and we live with the characters long enough to more fully understand them and the changes they undergo. A viewer who has not read the novel might well not be bothered by what sometimes seems to me a hasty treatment of some of the developments, and that's fine. And in this case, there is much that I do like about the series -- but its effectiveness for me is compromised by the director Jim O'Hanlon's conception of Emma herself. I don't think it's the fault of Romola Garai [pictured below, as Emma], who did excellent work in the BBC serialization of Daniel Deronda (she was Gwendolyn Harleth) and in the newsroom thriller series The Hour. In what follows, I'll discuss what struck me as the strengths and weaknesses of each of the three versions.

1. BBC series (2009).

There are two great strengths to this version. One is the scene-stealing performance by Michael Gambon as Mr Woodhouse, Emma's widowed, valetudinarian father, who is almost paralyzed by his fears for his own health and those of people he cares about (so he's not totally self-centered). It's a one-dimensional role, but Gambon is so alive and droll and charming that it doesn't pall. (I once saw Gambon on stage as Eddie Carbone in Miller's A View from the Bridge, very credible and scary, despite some slippage of the Brooklyn accent, and as far as could be from Mr Woodhouse.) Of the three Mr Woodhouses I'm considering here, he's the one for whom Emma's love and concern are most credible, and that's thanks to Gambon. More important, though, is the other strength -- the length of the series enables us to more fully appreciate the insensitivity that approaches cruelty in Frank Churchill's treatment of Jane Fairfax. In having to disguise his engagement to Jane, Frank's strategy, as I explained above, is to treat her disparagingly while showing a decided and quite public interest in Emma herself. Emma, to her discredit, goes along with this disparagement and seems even to enjoy it, though it's obvious that Jane is at least her equal in beauty and her superior in musical talent, even if she is a penniless orphan. Already resentful of Miss Bates's attention to Jane, Emma is completely snowed by Frank's deceit, and for a long time she even fancies herself in love with him. The two actors playing Jane and Frank, Laura Pyper and Rupert Evans -- names unknown to me until now -- are very effective, and Pyper especially makes Jane's suffering convincing. I think it's critical to our estimation of Emma and to our understanding of the moral force of the narrative to see as much as we do of the Frank-Jane relationship and its complications. What's galling about Frank, though Emma never seems to notice the impropriety of it, is Frank's obvious enjoyment of this game of disparagement. That's because Frank is witty and charming and draws Emma into enjoying it too.

My reservations about the conception of Emma herself in this version might be put this way: Emma is too like Harriett Smith, the protege whose romantic life Emma undertakes to manage. Harriet (Louise Dylan) is a pretty, good-hearted, not-very-bright girl, and her limitations are indicated by the readiness with which she accedes to Emma's ideas about her marital prospects. But Emma herself should not appear to be so silly -- she should (and in the novel does) understand that she is seeking to move Harriet into a higher social class and that doing so might prove painful to Harriet. But in this version Emma comes across as a rather empty-headed giggly "fixer" whose main difference from Harriet is the fact that she, Emma, has rank and money and the power that goes with them. In the novel, Mr Knightley's attraction to Emma derives in part from his perception of her her intelligence, a quality she undervalues or fails to acknowledge in herself, and it's important that in a filmed version this intelligence be somehow made manifest. In this version, however, Emma's matchmaking comes across not as a misuse of intellect but as mere meddling. Consequently, the scenes of Emma's dawning moral awareness lack the force that they could have.

One curious feature of this version is the opening, with its "backstories" that explain how Frank Churchill and Jane Fairfax came to be isolated from their respective families as children. I'm not sure how this is supposed to work, unless to suggest that Frank's bad behavior later is to be explained as a response to the childhood trauma, for Frank has always known the identity of his father. That father is Mr Weston, a neighbor of Emma and her father, who in the opening of the novel (and the other filmed versions) marries Anne Taylor, Emma's governess-companion. When a young widower and in difficult financial straits, he had given Frank up to be cared for by his sister-in-law, who insisted on the change of name to Churchill and who brought Frank up in very comfortable circumstances. Are we meant to see Frank's bad behavior as somehow intended to punish, by embarrassing, his father for "abandoning" him?

The rest of the cast is just fine, although there are more vivid performances of some of the supporting characters in the other versions. Mr Knightley is played by Jonny Lee Miller, very much against his Trainspotting type. He's effective enough, though perhaps not credibly sixteen years older than Emma -- Miller is in fact nine years older than Garai, who was in her mid-twenties when this Emma was filmed. Jodhi May, as Miss Taylor, is arguably too young for the role. In Daniel Deronda, where she appears again with Romola Garai, she is Garai's romantic rival. I think that she should be at least as old as Mr Knightley -- 38 in the novel -- but still younger than Mr Weston, whose wife she becomes. Of the others, Tamsin Grieg is a very effective Miss Bates, and Christina Cole a Mrs Elton that you love to despise -- even as perhaps you uncomfortably realize that she is, in many ways, a lot like Emma in her belief in her organizational powers.

Gwyneth Paltrow as Emma (1996)

The conception of Emma in this film version is much closer to that of the novel and, to that extent, preferable to that of the BBC serial discussed above. There is no doubt, either, that Emma is NOT just a giggly girl like her protege Harriet. The Harriet here is Toni Collette, a very fine actress [pictured above, with Paltrow], and the contrast between the sharp Emma and the dim but good-natured Harriet is perfectly clear. On the whole, Gwyneth Paltrow is a credible Emma -- she is not the most expressive of performers, a bit bland even, but then Emma is a character who sails through much of her young life untroubled by doubts about her motives or her machinations, and Paltrow's untroubled demeanor seems apt for much of the film. The big scene where she doesn't quite rise to the occasion is that of Knightley's declaration of love, where Jeremy Northam's rendering of Knightley's confusion and affection is credibly animated, while Paltrow doesn't seem able to find a matching animation in her own features. Three other women in the cast give more vivid performances -- Toni Collette, already mentioned, as Harriett, Sophie Thomson as a painfully vulnerable Miss Bates, and the great Juliet Stevenson as a surprisingly knowing, witty, and even likable Mrs Elton. There's also the accomplished Greta Scacchi as Mrs Weston, though her part, as written, doesn't give her enough to do.

As the list above suggests, there's an "all-star-cast" quality to this production, and it extends even to the score, by Rachel Portman. That's not to say that all roles are equally convincingly taken. The young Alan Cumming is too devoid of unctuous nastiness for Mr Elton, though he's always fun to see, and Ewan McGregor seems a bit uneasy as Frank Churchill. As I've already suggested, though, the Frank-Jane part of the story, with its important moral relationship to Emma herself, is diminished in this and the other film version, presumably in order to keep the film at a length deemed appropriate for showing in cinemas. Jeremy Northam is an effective, polished Knightley. Denys Hawthorne is an effective Mr Woodhouse, though less vivid than Michael Gambon in the role, and Polly Walker is fine as Jane Fairfax, even as one wishes that the full extent of her humiliation by Frank, and Emma's complicity in it, could have been developed more fully. The Frank-Jane story is much more than a sub-plot in the novel, for without a full treatment of it, we can't appreciate Emma's capacity for doing harm. That whole dimension is underplayed in this film, and together with Gwyneth Paltrow's blandness at crucial moments, it leads this version to be less morally engaging and affecting than it could have been.

Kate Beckinsale as Emma (1996)

As with the Paltrow version, this almost contemporaneous film also fails to give full weight to the Frank Churchill-Jane Fairfax story, the importance of which is to show us Emma's complicity in Frank's cruelty. In compensation, though, it does give us the most engaging accounts of Emma and of Mr Knightley, both given performances of great effectiveness. Kate Beckinsale's face, in repose, has a severity that suggests a person not altogether at ease with herself. She plays Emma as a character who could know that she is capable of using her intelligence and ingenuity to better effect than arranging the romantic lives of third parties in a small village. She comes across as not totally happy with herself even before the moral problems attendant on her meddling begin to be clear. It's fitting, then, that the Mr Knightley in this version, played by Mark Strong [pictured above with Beckinsale], is the severest and angriest Knightley of the three I'm considering, and to my mind the most effective. His Knightley is a blunter, less suave, more intense character than Jeremy Northam's, and his critical interventions with Emma -- with respect to both her meddling with Harriet's life and her climactic public insulting of Miss Bates -- have great dramatic force, and their impact on Beckinsale's Emma is palpably conveyed.

The rest of the cast is solid or better. Samantha Morton is as effective a Harriet as Toni Collette, and Prunella Scales -- yes, Sybil Fawlty from Fawlty Towers -- is a fine Miss Bates, older than the character in the other two versions and the more seemingly vulnerable for it. Scales was in her mid-sixties when she played Miss Bates, thirty years older than Sophie Thomson and Tamsin Grieg in their respective versions. Raymond Coulthard is a confidently assured young prig as Frank Churchill -- more at ease in the role than Ewan McGregor -- and Olivia Williams suggests a Jane Fairfax of considerable strength and dignity.

Some reviewers of this version saw it as an unusually "dark" film for an Austen adaptation. One can see their point, but that should not be seen as a criticism: rather it should be seen as a tribute to the film-maker's perception of the novel's moral seriousness. Austen is by no means always as "light and bright and sparkling" as she feared she was in Pride and Prejudice, and even in that novel, it's a mistake to see it as merely a frothy entertainment. If you want darkness in Austen adaptations, there's also the splendid and disturbing 2007 film of Mansfield Park, very strongly cast and directed by Patricia Rozema.

Epilogue: "But what about Clueless . . . .?

"Light and bright and sparkling" would do very well to describe Amy Heckerling's 1995 film, Clueless, but it shouldn't be taken as a version of Emma. The moral seriousness at the core of Austen's novel -- it's concern with impercipience that enables cruelty -- is totally excised. Plot elements are certainly borrowed from Emma, but the setting is moved to a California high school in an upscale neighborhood, and the Emma-like character, called Cher in the movie, is 16, where Emma is 21 or 22. Certain stereotypes of American teenagers are added to the mix, and it's all played for laughs. One of the big jokes on Cher is that her privileged self-confidence that derives from wealth blinds her to the fact that a boy she fancies, Christian (a parallel to Frank Churchill), is gay -- something that everyone else at her school seems to know. Still, the writing, also by Heckerling, is excellent, a mix of literary and pop-cultural allusion, high-school slang, and verbal invention ("As if . . .!") that the cast carries off just perfectly. Alicia Silverstone is the valley-girl incarnate, and if it's froth, the movie knows exactly what it's doing. Stacey Dash and Brittany Murphy as Cher's sidekicks [above , with Silverstone] -- with Murphy in the Harriet role -- are perfect partners. On it's own terms, the film works perfectly.

Sunday, October 15, 2017

Mahler's weird Fifth

Earlier today, I took a deep breath and committed myself to listening through all of Pierre Boulez's recording of Mahler's Fifth Symphony -- maybe the first time that I've really tried to concentrate over the whole span of its 75-or-so minutes. What follows are impressions only -- I'm not close to competent to make musical judgments. I can only report on what the music seems to me to express, and a more musically literate person than I would probably have a much more confident sense of what exactly is going on in this 5-movement structure that seems to me to be both compelling and deeply weird. Mahler's orchestration is so distinctive and transparent and his motifs are so engaging that I'm never bored when listening to his music, but it's work -- especially when one gets outside the more accessible, often folk-song saturated worlds of the "Wunderhorn" symphonies, especially the First and the Fourth (although they too have their weirdnesses).

The first thing that struck me, on reflection, was that the Fifth Symphony's first two movements might be thought of as "alternative" first movements. The first movement -- a funeral march, at least to begin with -- seems "public," a public engagement with grief and loss, such as one might associate with a ceremony like a procession to a graveyard. In Boulez's recording, it's close to 16 minutes, and hypnotically powerful in its opening measures, but long before the end of the movement, the sense of order falls apart and something much more desperate and painful erupts -- a reminder, perhaps, of what kinds of private sorrow the public ceremony fails to do justice to. There's an effort to get things back in order, but the final five or six minutes are roiled by the outburst and never quite recover their balance. The second movement seems broadly the private counterpart to the first movement -- "sturmisch bewegt" [stormily moving] -- much more unpredictable in its movement, with howls of pain interspersed with reminiscences of something more like the first movement's steadiness but also with quieter yearning moments. Musically, it doesn't seem chaotic -- no more does the first movement -- for the motivic development is quite transparent, even though one might not know just how the motives and their moods are going to be sequenced. But when the transitions come, we realize that we're hearing something recognizable and that a shape is emerging, though I, at least, have no way of naming it. In Mahler's designation, the first two movements make up "Part 1" of the symphony, so maybe it makes sense to see these two movements (about 28 minutes of music) as constituting a single movement of some kind.

"Part 2" is a 20-minute-long Scherzo (so designated by Mahler), and marked "Strong. Not too fast." It seems to me to represent or express an effort to lift the spirits, but you know that when you give 20 minutes to that effort, it's not working too well. The music here often adopts a"laendler" character reminiscent of the Wunderhorn symphonies, but the mood of freshness isn't sustained, and reminiscences of the first two movements impose themselves too. It strikes me as an unstable movement -- or, at least, heightening the sense of instability that haunts the first two movements too. What's expressed is a failure to settle, a failure to know what to do about the mind's unpredictable movements. The music isn't confused -- it's gripping, as in a soliloquy in a play in which a character reveals a chaos of feeling and thought -- expressing confusion without being confusing. The idea of the symphony's being dramatic as a whole is one that makes sense to me -- like those Romantic poems of inner turmoil in which the drama is the inner drama of the effort to effect a change in mind and mood.

"Part 3" is made up of the final two movements -- a ten minute Adagietto and a 15-minute Rondo marked "Allegro -- Allegro giocoso. Frisch [Fresh]." The Rondo succeeds in being lighter-hearted than the third-movement Scherzo, but for all that there seems to me throughout an undercurrent of uneasiness (buzzing basses), and the sense of instability isn't wholly expunged. The "fresh" music isn't assertive or triumphalistic (compare the end of the First Symphony), and it's often quite quiet, as if infected by a carry-over from the Adagietto. Still, it seems the right kind of conclusion for this particular drama.

I've left the fourth movement to discuss last, partly because it's one of Mahler's best-known and is often programmed as a separate piece. "Sublime" is a word often used of it, but when one hears it in context, that characterization seems wrong -- at least as referring to what's expressed. It might be a marvelous piece of musical construction, but to me it expresses the featureless flattening of affect that I associate with depression. Thus I think that Luchino Visconti was right to use it as he did in his film Death in Venice, where it is absolutely fitting for the depression and repression and sickness that Dirk Bogarde so powerfully and restrainedly conveys as Aschenbach, the dying artist [image above]. In Aschenbach, repression is perhaps one cause of the depression, being a denial of the erotic attraction of the "classical" beauty of Tadzio, the teenager he is obsessed with watching. Mahler's music, heard in context of the symphony, doesn't, of course, "mean" all that -- but Visconti saw that in the context of the movie its "meaning" could be extended to include that. But even without Visconti and the movie, the music doesn't convey "sublimity." It's just very, very sad, with the sadness that comes from a sense of the impossibility of lifting ones own spirits by an act of will.

Mahler's Fifth is a great symphony, and I was much impressed by Boulez's account. I had been surprised at how much I enjoyed his accounts of the First and Fourth, for I had thought of Boulez as something of a cold technician of music. Far from it. The orchestra is the Vienna Philharmonic, sounding great.

Note: The image that opens this posting is the cover of the 14-disc box of Boulez's Mahler recordings for Deutsche Grammophon. In addition to the symphonies, it includes the songs, Das Lied von der Erde, Des Knaben Wunderhorn, and Das Klagende Lied. All but one of the recordings are studio recordings, and the sound is excellent. I got it for just over $25.00. It's an amazing bargain.

Saturday, October 14, 2017

bachauer and brahms

The Greek pianist Gina Bachauer (1913-76) seems to have recorded the Brahms Second Piano Concerto twice in the 1960s, both times with the London Symphony Orchestra. The first of these recordings, with Stanislaw Skrowaczewski, was issued on the Mercury label in 1962, in its "Living Presence" series. Five years later, the conductor was Antal Dorati (who also recorded a lot for Mercury), and it is the Dorati recording that I picked up (for $3.00!!) on a Chesky CD at my local independent record store, Horizon Records, in Greenville, SC. Chesky Records has, since 1978, undertaken high-definition recording by complicated processes that I don't understand, like "dummy head recording," but it has also produced a limited number of reissues of older recordings in improved sound. Whether these improvements amount to "remastering," I don't know, and I haven't done comparisons with the original recordings, but these improved issues have been well received. In particular, it seems to be agreed that Earl Wild's recordings of the Rachmaninov Piano Concertos and Rene Leibowitz's Beethoven Symphony set have been benefited by the Chesky treatment. Like Wild's Rachmaninov and Leibowitz's Beethoven, Bachauer's 1967 Brahms Second was recorded originally for the Reader's Digest Association as a special issue.

In its Chesky manifestation on CD, it's a very attractive recording. Both the orchestral sound and the piano sound are very present, to a degree that doesn't realistically approximate a concert-hall experience, but since no recording really does that anyway, it doesn't bother me. The main thing is that the orchestral textures and the piano quality are both very vividly realized. Dorati conducts with great energy, and Bachauer's playing is robust to match. I don't know if there is such a thing, among women pianists, as a "feminine" touch, but there's nothing delicate or retiring about Bachauer's playing here. Like Martha Argerich's playing, it's vigorous and engaging, and since Argerich never recorded the Brahms concertos, maybe Bachauer's recording can be a kind of compensation for that gap in the catalogue. I have more recordings of the Brahms Second than I need, but at the prices of used CDs today, it's hard to resist. As a "filler" on this recording, Strauss's music for the Dance of the Seven Veils, from Salome is given a colorful performance, again with great presence and energy. This was recorded in 1962, five years before the Brahms but with the same recording team.

Another reason that I'm glad to have this is that it's my only Bachauer recording. She doesn't seem to have recorded nearly as much as Serkin, Ashkenazy, Arrau and other giants of her time, but her recording of the Brahms, at least, is as engaging as any of theirs. In 1981, the Greek government issued a postage stamp in her honor, and I have used it as the image for this post.

Thursday, September 14, 2017

Martha's Mozart

Among the great unanswered questions of life is why the great Argentinian pianist Martha Argerich (b. 1941) never recorded the Brahms Piano Concertos. Leaving that aside, it's noticeable that she didn't record much Mozart either. She recorded a couple of concertos for Deutsche Grammophon in 2014, with Claudio Abbado not long before his death. (Abbado had earlier recorded Mozart concertos with Serkin and Pires, also on DG.) Two decades earlier, though, Argerich had recorded two solo concertos for the Teldec label -- No. 19 (K.459) and No. 20 (K.466) -- along with No.10, for two pianos (K.365). On this recording, the sound is excellent, with plenty of presence for both orchestra and solo instrument. The orchestra in the solo concertos is the Orchestre di Padova e del Veneto, and the pianist/composer Alexandre Rabinovitch conducts. Rabinovitch takes the first piano in K.365, with Jorg Faerber conducting the Wurrtemberg Chamber Orchestra. The two-piano concerto has plenty of energy and charm, but the solo concertos are the main attractions here. These are spontaneous-sounding, muscular performances, with the left-hand writing given more weight than one usually hears, but there's nothing ponderous or scrappy about the overall effect. Argerich's playing of the Beethoven cadenza in the first movement of K.466 is alone almost worth the price of the disc, and the probing, almost improvisatory opening of the second movement is engaging and arresting. Throughout, the sense of interplay between orchestra and soloist is strong. K. 466 is a turbulent and brooding piece -- reportedly, one of Beethoven's favorites -- and it gets a great performance here, from both pianist and orchestra. You want to stand up and cheer at the end.

Wednesday, September 13, 2017

Solti's Beethoven Seventh

Back in the late 1960s, when I started trying to build up a collection of classical recordings, a new vinyl LP cost $16.00, more or less. I felt that I had to save up my pennies and buy wisely, usually guided by recommendations in whatever magazines I could find, and eventually guided by my sense, as my collection grew, of what I liked and what I liked less -- for had I had money enough then, it would have been nice to buy more than one recording of pieces of music that I found accessible. As it was, though, I stuck with Szell and Karajan for the Beethoven symphonies -- the 1960s DG Karajan recordings, that is -- and was sufficiently satisfied with them to refrain from adding other versions. As a result, recordings by Walter, Haitink, Jochum, and Bernstein went by the board, despite my having read positive reviews of some of them. It never occurred to me to seek out used copies. I assumed that they would probably be warped or scratched, as my own LPs tended to become over time. But the CD revolution changed all that -- used CDs can give excellent sound and will continue to do so long after I will be beyond hearing them. So it was amazing to me recently to pick up for under $3.00 ( and 2017 dollars at that!) a copy of Solti's digital recording from the late 1980s of Beethoven's Seventh and Eighth Symphonies. By this time, I had quite a lot of Solti's Wagner, Mahler, and Strauss -- and I enjoyed them -- but I had in mind comments I had read years ago about Solti's conducting being "tense" or "overdriven" in earlier music, and so I had never bothered with his Beethoven recordings with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Two earlier purchases led me to give his Beethoven a try: I had bought (also cheap) his recording of Mendelssohn's Third and Fourth Symphonies, and his first recording of Mozart's Cosi Fan Tutti, which I found very enjoyable. I like Beethoven's Seventh a lot, so I got it.