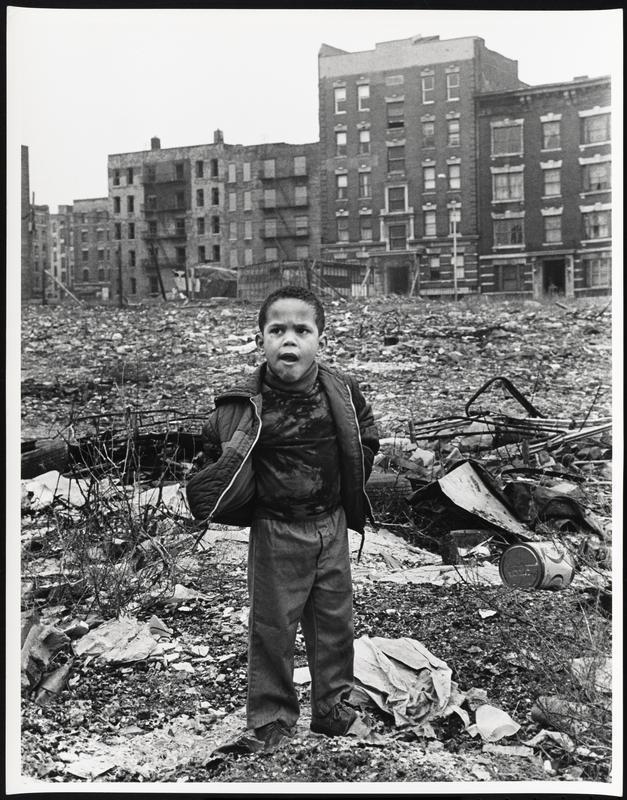

A couple of days ago, I was taken aback when I saw the substantial obituary for the photographer Mel Rosenthal in the New York Times. Our paths had crossed briefly about 45 years ago, and I had thought about him occasionally since, but I hadn't known of his success and reputation as a photographer in New York. It was heartening to hear of it, even though it was sad to hear of his death. [That's one of his South Bronx images, above.] I was teaching English at Vassar in the early 1970s and trying to write my doctoral dissertation. Mel had been in the department a few years -- he was four years older than I -- and he wasn't long for that world. Vassar had begun to admit men in 1969, the year before I started there, and the powers-that-were in the English Department at that time were largely older single women, not far from retirement, with a couple of middle-aged men just below them in length of service. The college was changing, the country was in the throes of anti-war and civil rights disturbances, the academic job market was beginning to tighten, and the atmosphere was tense. There were some very smart younger people on tenure-track, and there were others like me who were on a three-year contract with prospects of a second, and mostly my memory is of the younger generation keeping their heads down, being appropriately deferential, and beavering away to establish themselves in the profession. Only two people in any way ruffled the surface: Harriett Hawkins, sharp as a knife and flamboyant as hibiscus, had a book out from Oxford University Press and was untouchable; Mel Rosenthal, direct, outspoken, aware of a larger world outside the college, was more like an irritant. In department meetings, he spoke out in the sterile arguments about things like "the integrity of the two-semester course," and spoke with the confidence of himself as the intellectual equal of anybody in the room. I wouldn't say he was rude, but he didn't do deference. He had a sense that the department could be doing some more interesting things in addition to the then-standard canonical stuff that comprised the bulk of the curriculum and he wasn't afraid to say so. I have to say that I know nothing about his effectiveness as a teacher or whether or not he had potential as a literary scholar. I had been at Vassar a year or two when he was fired. In a famous scene, he stormed out of the (male) Chair's office after having been "let go," and, to the horror of the genteel department secretary, flung back over his shoulder a couple of obscenities and the word "pipsqueak."

At the end of my first year at Vassar, the English Department hired a young black man (I'll call him Fred) whose field was 18th Century literature. He arrived in the summer before he was due to start teaching -- I think the summer of 1971, but maybe 1972 -- and almost immediately suffered some kind of psychological or emotional collapse. I never did hear the official diagnosis. At that time, my wife, Janis, and I were living in college housing at the back of the campus near the golf course in a building called Palmer House that comprised five or six apartments, and Fred was to live in one of them, next door to us on the second floor. At first, he seemed friendly and a bit reserved, but it wasn't long before we found him one day cowering in a corner of a room in his yet hardly-furnished apartment, apparently terrified of something. Shortly thereafter, he was picked up one night by the college police, out of doors near our building and shouting into the darkness. Some nearby neighbors had heard him (we hadn't) and called the police about the disturbance. When we next saw Fred, he was in some kind of facility, in downtown Poughkeepsie, I think, and undergoing treatment.

Janis and I went down to see him with a friend, Tom Duddy, who was also a friend of Mel's, and when we got to the hospital, Mel was already there. I have a memory of a large room with green vinyl-topped tables and cream walls. The tables were bolted to the floor, and so were the chairs, so that when one sat down, it was impossible to pull up the chair or pull the table closer. Fred sat in a chair, subdued and, I assume, medicated. He seemed embarrassed, maybe ashamed, and had little to say. It was uncomfortable. Janis and I had certainly never seen anyone in such a condition or in such a place, and it was hard to find words. I have no idea what we said. I do remember that, of the four visitors, Mel was the one who found the most to say, and I was struck by his directness and gentleness. For all I knew, he was as uneasy as the rest of us, but he found a way of trying to engage Fred constructively. He had no illusions, though -- as became clear as we were leaving -- about the likelihood of Fred's taking his position at Vassar. The blend of gentleness and clear-sightedness was what I've remembered on the occasions over the last four decades whenever I was reminded of Mel, which wasn't all that often because I hadn't been close to him.

I don't know what happened to Fred -- a severance with Vassar was arranged -- and I didn't know, until I read his obituary, what had happened to Mel. I'm pleased, though, that he was successful and respected. He was a good man, and I like to think that his work is in some way consistent with the behavior he exhibited that day in that miserable green-and-cream room.

No comments:

Post a Comment